|

Decoding the mise- en - scènes of Medieval Christian Spirituality and Contemporary Consumerist Lifestyle

For the first time, follow the directions in the accompanying audio file. Later, you can use this index for links to the various subsections in the material.

The key principles underlying this comparison between two very different cultures at different periods of history

While the differences are significant and important to note, both have been dominated by a universal visual iconography that mediated powerful cultural sources of meaning and values; these were like the pillars that structured a unified social reality for the people of the time, shaping their views of meaning and purpose to life. The dominant cultural imagery in both situations conditioned the perceived underlying narrative or mise- en -scène for life.

This comparison is an unusual, but useful way to identify and evaluate spiritual and moral dimensions to contemporary lifestyle.

As noted in earlier study, in Medieval Christian times, living was interpreted from an almost exclusively religious perspective.

1. How the mise-en-scène of traditional, medieval Christian spirituality was sustained by religious artefacts

| The works of religious art in early medieval Christian churches were more like films than paintings because of their religious story-telling and symbolic purposes. They were both narrative and symbolic/theological in their meaning. Christians got many of their religious cues from them. The content of practically all the art they could see was religious (This changed after the renaissance when more humanistic material appeared). In large letters above the main entrance to the duomo in Cittadella, Italy are the words Domus Dei et Coeli Porta – The house of God and the gate to heaven. |  |

This summed up the place of the church in the lives of Christians at the time. A sense of connection to the spiritual/religious world came through the religious artistry. It reinforced their beliefs because there in front of them was imagery that reminded them of what they believed in and it gave a sense of communal assurance and validation to those beliefs. For those who did not travel extensively, and this was the majority, the religious world depicted in their churches described their small universe. They drew on its religious imagery to understand that universe and their place in it.

At least six different types of religious message-communicating formats can readily be identified in medieval European religious art.

| 1. Narrative depiction of biblical events and stories from the Bible, both Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. They chronicled the events of Christian salvation history and served to imaginatively connect the present Christians with these saving events. |

|

||||||

2. Linking current religious practice with salvation history. This emphasised the making present again of the saving action in the original events. For example: Baptismal font. |

|

||||||

3. Locating Biblical events in the local landscape. Events in the life of Jesus like the infancy narrative, the crucifixion or the deposition from the cross painted within a readily identifiable local landscape – E.g. Bellini paintings in Venice and elsewhere with the recognisable profiles of local towns and churches as the background location. |

|

||||||

4. Locating local saints and religious heroes within the Biblical events. Symbolically making the saving events present again and reconnecting with the original were illustrated by having well known and venerated recent local saints depicted as being present. For example: Saints Francis and Anthony adoring the Christ child along with the Magi. |

|

||||||

5. Locating key local political and power figures in the Biblical stories. This went beyond connections through key saints to include local people in the Biblical story, especially the rulers and nobility. This sort of inclusion had a long history as illustrated in the 5th century mosaics at San Vitale in Ravenna where the emperor Justinian and empress Theodora were given prominent positions in the religious pictures. |

|

||||||

| 6. Key saints coming back to make saving interventions. This highlighted the religious power of the saints in present times when they came back and effected change. E.g. In Venetian paintings St Mark who came back to confound the Muslims with his theology, and in another instance to rescue Muslims from a shipwreck. |

|

||||||

|

|||||||

The subject matter of the art was spiritual and religious. It was a visual narrative theology. It called for reflection and meditation – and in turn, review of personal life in relation to the transcendent. It constantly reminded believers of the bigger picture that this life was just a preparation for the next life after death. It was intended to inspire awe, adoration and devotion. Also prominent was fear of the devil and of going to hell for all eternity – a powerful motivation to live a moral Christian life.

The art identified primal religious heroes and role models for faith in the biblical and historical records – Jesus, Mary, Hebrew bible heroes, the Apostles and Christian saints. In addition, a cult of relics developed where the remains of saints were revered as sources of religious power that was protective, enabling and miraculous. Also art-related was the religious pilgrimage to holy places. Religious rewards and remission of sins were associated with pilgrimages. Pilgrims got identifying badges showing the successful completion of their devotional journeys. In villages, small mini-pilgrimages to a church outside the town, often up a hill, were instituted; even those who could not travel the notable pilgrimages then had their own small town option.

The art also served to remind people of their shared Christian beliefs, helping give them a sense of faith community. It complemented the religious rituals of belonging and helped communicate a sense of religious identity. The prominence of clergy and religious communities reinforced the social, political and religious stratification of society; the social structure was hierarchical and power-dominated. Everyone had their place from birth – their station in life; and relatively few could change their position in that network. Joining a religious order or the priesthood could change social status considerably for any who were low down in the social order.

The visual religious imagery called on believers to reflect on their valued place in the divine universe and in the Christian church. This pointed them towards a deeper meaning to life beyond its surface level. They were reminded of their affinity with the saints and fellow Christians.

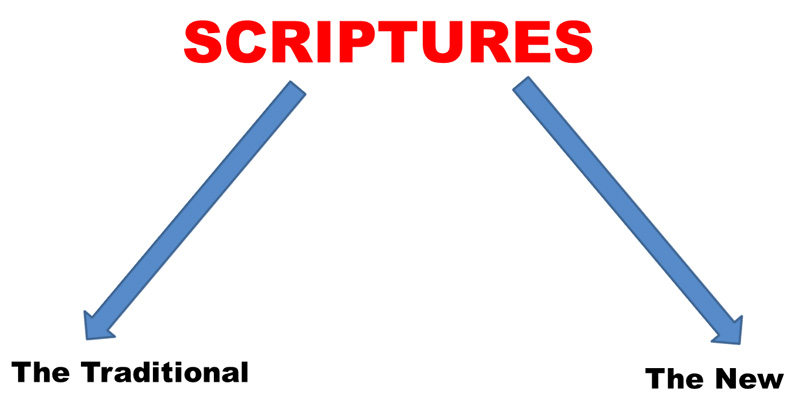

Christians' access to the biblical texts themselves depended on their level of literacy and education; most were illiterate and therefore more dependent on visual imagery as their main record of salvation history. The bible remained the central identifying cultural artefact of Christianity. It became even more prominent after the Reformation and the inventing of the printing press, when popular access to the bible first developed.

The church bells were the aural reinforcement of the visual architectural dominance that the local church had in the village, and in the larger cities by the cathedrals. The bells, especially at Angelus time, divided up the day's time periods. Time was also partitioned according to the hours of the Divine Office celebrated in the monasteries. Sunday was by God's decree the day of rest and religious observance. Mass and religious rituals complemented the narrative theology in the artistry. The liturgical cycle organised life around the remembrance of religious events and the festivals of saints; these celebrations were like re-enactments of the events making for reconnection. In a sense, the prominence of religious art signified a society that was ‘overdosed' on religion.

2. The popular cultural imagery in contemporary Westernised societies that mediates a different mise-en-scène

The religious imagery that sustains a traditional Christian spirituality as well as more contemporary versions is still available for those who choose to relate to it. For many secularised Christians and those who are not religious in any way, there is a wealth of visual imagery in popular culture that suggests how life could be lived and which informs their spiritual mise-en-scène. Contrasts will now be drawn with the medieval model, with questions asked about how the various elements described above might have parallels, with similarities and differences. Keywords in bold type will identify the comparisons. Some comparisons are more plausible than others; this variance is the down side of a useful pedagogy that highlights significant differences in the way imagery is used to envision the good life.

While the images to which people are exposed today include much that is informative and educational, here attention is given only to the imagery concerned with lifestyle. Because it looks towards the potential problems with excessive and naive responses to meaning-making imagery, this analysis can appear negative and biased; this is the un-intended impression that can come from an approach that is purposefully diagnostic. The notes on the comparisons will be brief, trying to give a general picture by signposting an iconography that needs more detailed analysis to interpret and explain how it mediates spirituality.

|

The 'new' religious narrative theology. Omnipresent in imagery out of doors, at night, in film, television and advertising -- and on your own computer, mobile phone and tablet. Click the photograph or here for video of contemporary 'religious' imagery. |

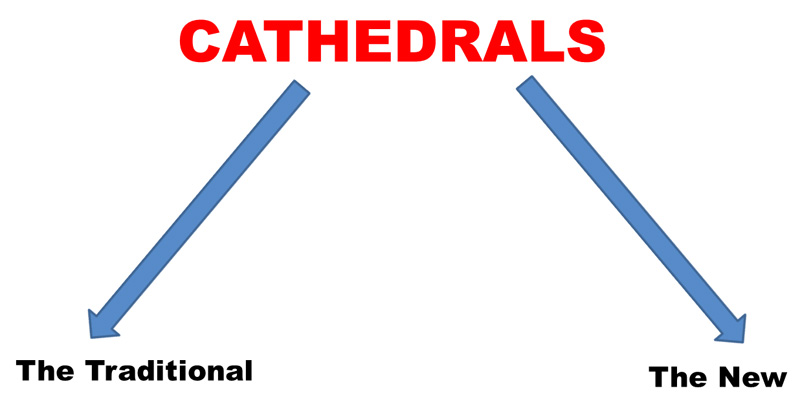

3. The Old and the New 'Cathedrals'

Domus Dei et Coeli Porta. An obvious parallel to the cathedral and church is now the shopping Mall or Designer Outlet centre. Whereas medieval Christian imagery concentrated on the spiritual/religious dimension as the inspiration for journeying faithfully through daily life towards your goal in heaven, now the imagery, especially from the consumer/advertising industries, is directed towards getting the most out of life right now – that is, exclusively concerned with lifestyle, consumerism and entertainment. As the song said: “I want it all, and I want it now.” (By the British rock band Queen from 1989.

As consumerism reaches increasingly beyond the acquisition of things to the enhancement of the person, the goal of marketing becomes not only to make us dissatisfied with what we have, but also with who we are. As it seeks ever more ways to colonise our consciousness, consumerism both fosters and exploits the restless, insatiable expectation that there has got to be more to life. And in creating this hunger, consumerism offers its own remedy – more consumption. (Eckersley, 2006, pp. 11-12)

The church was regarded as the "house of God and the gate to heaven" |

Click the photographs for videos showing the contrasts

Dominance of religious culture. In medieval Christianity the culture was dominated by religion with its dominance reflected in religious imagery. Religion pervaded ordinary life. There was little opportunity to deviate from the religious system. But today there is considerable diversity in cultural meanings and individuals have choice as to those to which they will subscribe. Religion has little prominence in popular culture and imagery, and where it does figure, the image tends to be negative (Fenn, 2001; Martin, 2005). Christianity is regarded by many as out of date and largely irrelevant. And the prominence of Islam is perceived as in a worrying clash with Western civilisation.

God and church. For traditional Christian faith, God was considered to provide the overarching authority, the source of authenticity, and the verification of absolute certainty for the believer. And this was mediated on earth through the church. Now, for many people, it is the personal self that has taken on board this powerful role. Individuals will decide themselves what to believe, and even what they think is true in the spiritual domain (Hughes, 2007). For a number who still identify themselves as nominally Christian, the church has taken an advisory role as an optional, background infrastructure for meaning in life (Hughes, 2007; Rossiter, 2011A).

There is no room for the idea of God as a supreme being in consumerist lifestyle. But through the experience of extravagance and luxury, individuals themselves can feel like they are being treated as ‘gods'.

For children growing up in a secularised culture, some may not hear the word ‘God' until they go to school. Or they may hear it from their parents or friends or on television in the form of an expression of surprise or exhilaration “Oh my God!” when something wonderful happens. In her research on children's prayer, Mountain (2004, pp. 114, 141) showed that this expression sometimes confused children who wondered whether “Oh my God” was intended to be a prayer. What was once a core phrase in religious faith has become secularised into an everyday expression. OMG has not only become an acronym in texting and social media, but even a brand name for clothing and fashion outlets (E.g. OMG and Pinterest, 2013. More than 8.4 million hits were recorded for the Google search “Oh my God” fashion. When experience is substituted there were 20.9 million, with 5.3 million for faith and 5.5 million for religion.)

Religious art. In modern times, art is no longer limited to the churches, galleries and the dwellings of the rich. Almost everyone can adorn their homes with their own choice of art. But more prominent as the major source of contemporary imagery is film, television, and ICT (information and communications technology) including the social media. People can now create their own personalised imagery and texts and post these to social media.

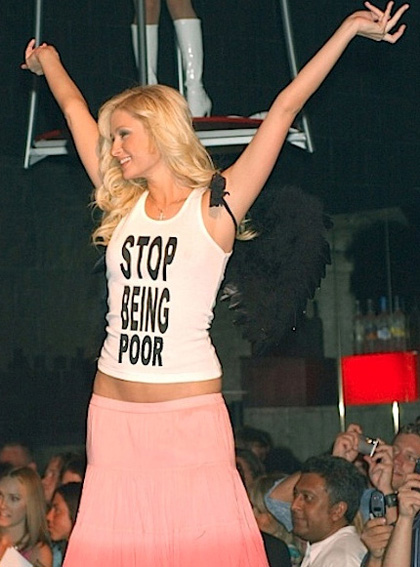

Clothing has long been art-related to some degree. In the past, people wore set colours, uniforms and traditional dress to celebrate and reinforce their sense of individual, local and national identity; and this still happens today to a lesser extent. Now people feel a need to have their own distinctive, personalised style of dress, even if from a commercial point of view they are in fact conforming to the uniform that the marketers are proposing as uniquely individualistic styles. Personal statements are also made on clothing (in addition to the branding); for example, Tee shirts have become renowned for displaying messages; you choose what message or statement you want your clothing to make. The Italians have invented a new type of shop to cater for making your own personalised Tee shirt statement – the Teeshirtaria.

The messaging and self-identifying personal statements can go even further because today you can readily have them engraved on your own body. Tattoos and body marking have a long tradition in some cultures. The use of identity mediating tattoos and body piercing has now become more universal and more popular. In addition to giving a sense of distinctiveness, it also signals belonging to a tattooed brigade.

4. The old and the 'new' Religious Narratives/Stories

Just as has been the case since the dawn of human history, meaning about life is communicated in story form and often visually. In medieval Christianity before the Renaissance, all of the visual narratives were religious. Film, television and ICT are now the principal story tellers, and hence they have become the major spiritual and moral reference points for people, displacing religion which tends to get little if any mention in the prominent narratives of popular culture (Crawford & Rossiter, 2006). Every media narrative, even the 30 second commercial, has an implied world-view. And constant exposure to the implied mise-en-scène of the advertising consumer complex may have a significant influence on the development of a personal mise-en-scène. People can readily end up mirroring the dominant media value system to which they have been exposed. Subconsciously, they can adopt a consumerist orchestrated sense of personal identity that plays out in a prominent way in their behaviour – especially their retail behaviour.

The Hebrew Bible |

|

These days you can even make statements on your own body about your personal meaning and sense of identity

With the social media, individuals themselves have become the authors of their own visual and textual stories; they script their day to day experience and adventures for anyone and everyone to peruse, constantly updating their digital persona, and even being able to monitor their scoring of ‘likes' as a measure of validation.

Research on the personal and social aspects of social media is growing rapidly. To note only a few examples: Personal effects of the new communications technologies (Giddens et al. 2011); Potential influence on group identity and self-esteem (Barker, 2009); Reduction in social involvement and well-being (Burke et al., 2010). Time spent on social media can impact on personal relationships and lifestyle. A report in The Guardian newspaper noted:

A study has found the average British adult spends more time gazing at their smart phones than their partner's eyes. While smart phone owners typically have 97 minutes a day with their loved one, they devote a full two hours to their phones, according to research by O2 and Samsung. (Garside, 2013)

Interestingly, of 16 different functions that people can engage in through their smart phones, making a telephone call comes in only as the 5th ranked activity (The Blue, 2012). How the use of mobile phones has evolved!

Today it is not uncommon to see almost every pedestrian in a group involved with their smart phones – texting, browsing, watching TV, listening to music (perhaps with headphones), playing a game, or even talking to someone. Seeing two people conversing or holding hands can be the exception. Many cannot stop fingering their phones for a few seconds as they cross a street corner. One journalist commented: “Almost every idle moment can now be relieved with a sneaky peek at your phone. If boredom is an itch, we scratch it with our smartphones.” (Freedman, 2011). Part of the problem is that people have become so accustomed to being digitally distracted by trivia that they seem unable or fearful to spend even a minute with just their own thoughts. The potential problems are not just psychological. The accident rate for pedestrians is increasingly being attributed to distraction during smartphone use (Wyle, 2013). The situation in the United Kingdom was reported as follows:

Children crossing the road are “distracted” by texting friends, “tweeting” messages, surfing the internet, playing games or visiting Facebook instead of paying attention to traffic. Alarming new statistics reveal that serious road accidents involving young children are at a ten-year high – particularly among girls.

A third of 14-year-olds “reported that they were distracted when crossing a road due to using personal mobile technology.” But the problem starts much earlier. “By the age of ten almost half of children have received their first mobile phone,” says the report. “By age 12, 73% of children have a mobile phone. More significantly, they use their mobile phone functions much more than younger children do. Because of this 25 % acknowledge that they themselves have been distracted by personal technology when crossing a road.” (Massey, 2013).

5. Shrines, relics and pilgrimages

Previously, the relics of martyrs and saints were revered with devotion for their spiritual power that could help individuals save their immortal souls. Relics were greatly prized by local communities, giving medieval cities/towns a pre-eminence related to the importance of their patron saints; they were even motives for war (For example: what were believed to be the remains of St Mark were stolen from Alexandria by the invading Venetians).

Today's consumer shrines are regarded as having considerable power to make people feel good in this life – consumer heaven is here and now. The new ‘powerful relics' are bought (paralleling the ‘indulgences' in the late middle ages?) and taken to their new homely shrines, where ownership conveys personal satisfaction, status and cachet. The large branded paper and plastic shopping bags, as well as the badged purchases themselves, are like the old pilgrim badges signifying a successful pilgrimage and the and acquisition of new relics. The metropolitan bus tours to the Outlet and Designer Centres are like contemporary pilgrimages to the consumer cathedrals. Visiting your local mall is the mini-pilgrimage.

The traditional Christian religious pilgrimage Pilgrims make a journey to a special religious place -- usually the shrine to a particular saint. Often there might be relics of the saints in the Pilgrim church. The purpose of the pilgrimage is to get closer to God through the experience. It is the spiritual journey. Sometimes it involved doing penance. St Alban, a Roman citizen, was the first English martyr and saint. His tomb is enclosed in the Cathedral of St Albans north of London. And it has been a place of Christian pilgrimage since Roman times. The Canterbury tales written by Chaucer tell the individual stories of the pilgrims on their way to Canterbury Cathedral. Canterbury became a special place of Christian pilgrimage in England after the martyrdom of St Thomas Becket who was killed in the Cathedral at the instigation of the King Henry II. The Camino is still a very prominent pilgrimage route followed by many people to Santiago de Compostela in northwester Spain.

Santiago de Compostela. The cathedral church and a map showing one of the Camino routes west across Spain to the shrine.

|

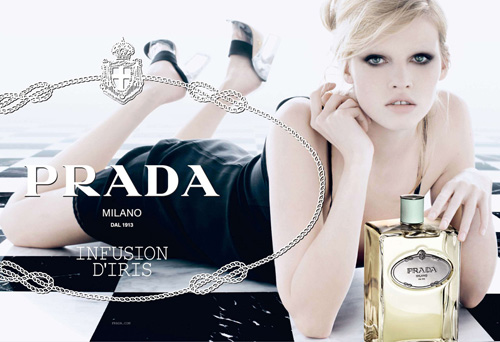

The contemporary consumerist pilgrimage The consumerist pilgrimage is to the consumerist cathedrals – special places where consumerism is worshipped and practised, especially through the prominent brands that are revered for the status and cachet they confer. The factory outlets and department store sales were prominent places of pilgrimage; but now special pilgrimages have appeared -- the more prestigious "Designer outlets". But most prestigious of all are the "formula one brand" outlets -- for example Prada. Just as the signposts tell you where the cities and towns are in the world, so it is important to know the signs of the principal brands. if you know these, then you know your way around the world. A pilgrimage to the designer Outlet or design Mall can be one of the few family outings these days that cater for the needs of all members of the family -- perhaps like going to church in the old days There are restaurants of all types available, including McDonalds. There are playgrounds for the children . The adolescents, the young adults and the more mature consumers can all find plenty of outlet shops with things they like and are interested in. Even if you don't buy anything, it is a place where you can see the luxury to which all people seem to aspire, and you can look at the various goods you need to display a successful lifestyle. It is a pilgrimage that reminds you of what life is about.

The Designer Outlet Mall. "Heaven is here and now". Click the photograph or here for a view of the pilgrimage.

The ultimate pilgrimage -- the Prada 'Space' Outlet at Montevarchi near Florence

|

In the extreme, some people travel overseas on consumer pilgrimages. One woman noted on the Trip Advisor website that she makes an annual visit from the United States to Montevarchi in Italy to get a complete new outfit from the exclusive Prada Outlet. It is so ‘high end' that it is not even advertised in local street signage like other outlets. Below are personal testimonies from two Italian ‘pilgrims':

Everyone likes to be well dressed. And if the clothes have a top label, it's the best. The gorgeous little Prada symbol never goes unobserved. Better than the usual cheap 30 euro slacks; at the Prada outlet these are 40 to 50 times more beautiful. Very beautiful bags that will enrage my friends.

I adore this outlet. It is organised; there is a vast selection of bags, wallets and accessories from Prada and Miu Miu. You don't know where to look or where to start. Every dream has become a reality. Because for just 500 Euro you can buy a leather Prada bag.

(Translated from Italian comments on the Trip Advisor Website 18/04/13)

And this is the exclusive club you get to belong to, and with which you can be identified (or badged)

|

|

Celebrities and film/tv/sports stars seem to have become the modern saints. By following their doings people can feel somehow connected with celebrity. Also, the modern saints are the icons of fashion and tastes. But there can be a down side to this hero worship when people have an ongoing feeling of low-level anxiety because they know they will never measure up to the standards set by the stars when they are continually confronted by

Just as in the past people read the lives of saints for their spiritual edification, now they can follow the trails of their celebrity icons in detail through both television, social media, newspapers and magazines – especially women's magazines. A new industry, the paparazzi, or photojournalists, operate to keep up a steady supply of photographs of today's saints for publishing in magazines or online. |

Where are they all now? List must be updated every year. Who are your 'saints' in 2021? |

The private lives of the saints are now more publicly available than never before. They may well be helpful role models. How much time and energy goes into following today's saints becomes an issue for psychological health.

With people now projecting and self-publishing their own image on Facebook and Twitter, they too can aspire to stardom and sainthood even if in a limited way. They do not have to be selected for a reality TV program to achieve stardom.

7. Some other comparisons between the Medieval Christian spirituality and contemporary 'consumerist religion'

It is interesting to speculate further about the parallels and differences one can find if the two meaning systems and life practices are compared under a number of other religious headings.

For example, the religious elements:-

Prayer, reflection and meditation

Priests

Sacraments

Real presence of Jesus in the Blessed sacrament

Feast days

Religious indulgences

Heaven, hell and purgatory

Guilt, sin, forgiveness, redemption and faith

Stations of the cross

Novenas

It is not that there are correct answers for the comparisons. The parallels may even seen frivolous and perhaps amusing.

Some tentative ideas emerging from such comparisons is given in this linked webpage.

8. Summary of contrasts: Mise-en-scène in traditional/religious and contemporary/consumerist spiritualities

For medieval Christianity, the dominant narrative about life was spiritual and religious. It was directly concerned with the spiritual realm and the next life. People were called on to look beyond present life to its eternal consequences. God himself through the church validated the socio-religious structure of society. The mise-en-scène was about the ‘economy of salvation'. Asked about one's identity, the answer would have included: I have an immortal soul created by God; with the help of Jesus, Mary and the saints, and through the church, I can save my soul.

By contrast, the dominant mise-en-scène today is almost exclusively concerned with the here and now. The iconic lines to the current official Pepsi Beyonce video encapsulate this: “Embrace your past; but live for now”. (Beyonce, 2013 Click here or the photo for part of the music video). If there is an afterlife, then that is a bonus, but it is not something towards which this present life is subordinated. The words ‘contemporary secular spirituality' have been used to describe the situation. But the word spirituality is not fully appropriate; rather, the modern mise-en-scène is about lifestyle. Because all lifestyles, no matter how secular, have implied values and meanings about life, one can infer that they also have an embedded or implied spirituality; so it can be like a spirituality by default. But spiritual or spirituality would not be the descriptor that most people would choose to describe their lifestyle or outlook on life. Their answer to a question about identity might be likely to make reference to the following: What brand of smartphone they have; how well their social media account is projecting their desired image; and what is their status/popularity score in terms of ‘likes', ‘friends' and ‘followers'. |

It is unlikely that the clock can be turned back towards the spirituality of the medieval mise-en-scène. Hence, religious schools hoping to educate and enhance the spirituality of their relatively non-religious students (and this refers especially to religious education), need to explore more proactively the existential quality of contemporary spirituality. Religious education needs to help young people learn how to identify the values and meanings implied in all aspects of contemporary life, and how to appraise them in the light of wider community values. For many young people, this is where their spirituality is located. Hence it is argued that this approach should have a more significant and valued place in religious education curricula, especially in Australian Catholic schools where the religion curricula still tend to be more or less aligned with a traditional Christian spirituality. This proposal is contrary to the views of those who think that religious education should remain more or less exclusively concerned with formal religious content, and not with content that is more focused on personal development and on contemporary personal and social issues that do not appear to have an overt religious component.

In the history of school religious education in English speaking countries, both in state and religious schools, there has been a well-established view that studying religion is linked with the personal development of students. For example, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, one expression of this linkage, dating from the work of Grimmitt (1983), that is still prominent today is that religious education should be concerned not only with students' learning about religion but also with learning from religion in ways that enhance their personal development (Byrne & Kieran, 2013). But in most contemporary religious education, the content is still concerned mainly with religion. And as noted above, some consider that venturing too far from religion into personal development content is straying from this religious focus. But if the view of Kuhns (1969) about the entertainment milieu functioning like a religion, and the follow up argument here showing how contemporary consumerist lifestyle is like a pervasive religion, are both given credence, then one could argue that it is pertinent to religious education's natural focus to study critically this new ‘religious' phenomenon.

9. Further sociological notes on global consumerist culture for evaluating its spiritual/moral dimension

This concluding section expands the commentary about contemporary consumerist lifestyle. It suggests that students could engage in small mini-research projects that explore the sorts of contemporary issues discussed here. This might help them develop their own critical interpretation of how media imagery orchestrates the underlying mise-en-scène or the metanarrative that underpins consumerist lifestyle.

Teasing out the mise-en-scène of contemporary lifestyle

To appraise the spirituality/values dimension to the mise-en-scène of contemporary secular, consumerist lifestyle, some understanding of the psychology of contemporary globalised consumerism is needed. Again, special attention is given to the mediating visual imagery. Icons at one end of the spectrum are the beverages/food giants like Coca Cola and McDonalds. They can be found almost anywhere on the planet from Eastern Russia to the Tunisian desert and South America.

|

Big brands create the consumerist atmosphere which we breathe all the time |

|

The story of how Coca Cola changed the image of Christmas -- an example of the impact of the big brands on culture |

Then there is a comprehensive range of consumer products, usually produced in countries with the cheapest labour and marketed globally. At the other end of the spectrum are the exclusive, designer luxury brands. These are like the ‘Formula One' of consumer products; they have the top status and they set the bar for consumerism that plays out differentially across the rest of the spectrum; they highlight ‘in bright neon lights' the taken for granted contemporary belief in the quest for happiness and personal identity through the buying and possession of designer goods. It is this latter area that will be considered here because it demonstrates principles that apply to varying degrees across the range. While not exhaustive, this partial analysis is proposed as an example of the sort of educational inquiry that is needed in the evaluation of contemporary lifestyles.

10. From bespoke for the wealthy towards designer status for whosoever can afford it

In earlier centuries in Western countries, it was only the wealthy who had bespoke clothing and luggage etc. made for them; bespoke was the badge of nobility and the very rich; only they could afford it. All of the items were one-off productions. For example, in Bond Street in London, there are shoe shops that still have the wooden casts of significant people for whom they made shoes in the 17th century to the present day. An example of costs: some today get bespoke watches made for them at costs above $20,000. Bespoke Birken handbags could cost $20,000. There is a waiting list of about 10 years for hand-made bespoke cars.

Formerly, this bespoke luxury was only evident amongst the wealthy. It was the taken-for-granted way they lived and the way they defined themselves to their peers. Anyone else who tried to dress ‘above' their given ‘station' in life was regarded disdainfully as a parvenu – someone who had recently come ‘into money' but had no ‘culture' or ‘breeding'. But more widespread consumerism has changed this.

While the very exclusive bespoke consumerism remains, there has been a shift in production and marketing by the premier brands to make their exclusivity and status more widely available to whoever can afford it. The higher levels of discretionary income across the whole population have been targeted by offering designer cachet for all; and the desire for this cachet is widely promoted by ubiquitous advertising. Research indicates that both the rich and poor have the same strong aspiration for designer branded goods.

The cry for riches to fill the existential void is not of course a wholly modern phenomenon. For centuries it has been understood that the hope invested in material wealth can only turn into greater hope, leaving happiness a dream. . . .But whereas this futile activity was reserved for the few in previous ages, today it is the province of the mass of ordinary people. (Hamilton, 2003, p. 78. See also Crawford & Rossiter, 2006, p. 156).

The premier brands try to retain a mystique of exclusivity and individuality (tapping into personal identity needs for distinctiveness) while at the same time catering to globalised markets. The trade-offs between exclusivity, price, image and industrialised production costs are carefully worked out. Abercrombie and Fitch were criticised for not making clothing for overweight people – they did not want ‘fat' people to be seen wearing their brand. (McNally, 2013).

Another strong suite in this brand mystique is that possession of the ‘branded gear' signifies that you are part of the exclusive club – you are ‘badged'. For example: women with Prada handbags have been seen turning the bag so that the triangular Prada emblem can be readily seen and identified; they assume that this label implies identification and recognition of their status and good taste. There are parallels in those with expensive sports cars; clubs of sports car enthusiasts exist where ownership provides entrée.

There are parts of the shopping precincts in most modern cities where the exclusive label brands live. International status is achieved when they become fixtures in the designer label set. This process occurs because people all round the world learn to desire their products; their status is universally acknowledged in different cultures. If they were not marketable and did not develop their international status, they would not last long. The distinctive designer brand clubs cross national and racial boundaries. Australian companies such as Ugg, Elle McPherson and Billabong appear to have achieved some international repute as designer brands.

11. Why do people shop to buy designer status?

This question needs to be explored to identify the core psychological processes at work. Basically, people have become accustomed to wanting designer goods because possessing them makes them feel good. Perceived high quality ‘stuff' has become an important external identity resource. In times when consumerism is both promoting and targeting ‘congenital identity deficiency' (Crawford & Rossiter, 2006, p. 121), people have been persuaded that having a well recognised quality product enhances their sense of self-worth – and this registers on their feel-good indicator. This was evident in a segment from a recent documentary where a young Japanese woman living in a tiny apartment said that she felt escape and relief from her bleak home / work situation when she went out wearing her Gucci clothes and accessories – these made here feel great; she was also gladdened by identifying some sense of ‘sisterhood' with others who wore the same ‘gear'. Also, she had her branded items significantly placed in her apartment to remind her that she owned them and to reinforce the feel-good associated with them.

A ready reminder of the luxury designer brands comes through looking at the pages of a magazine like Vogue Knowing you have luxury goods can convey feelings of power and status, signifying that you have ‘made it' in the wealth stakes. They can signal where you stand in the social pecking order. They can compensate for felt personal and physical limitations. |

|

Quart (2003, p.31) noted that the teenagers who were most obsessed with designer labels tended to be those who felt they were not conventionally attractive and who needed to compensate by ‘branding' themselves. A similar example: shorter men apparently needed higher incomes to equal the marriage potential of taller males (Whitbourne, 2013).

Consumption no longer occurs in order to meet human needs; its purpose now is to manufacture identity. The nature of consumption spending has changed from an activity aimed at acquiring status through displays of wealth to one of creating the self through association with certain products and brands. We no longer want to keep up with the Joneses; we want to trump the Joneses by differentiating ourselves from them. . . useful goods [have been transformed] into lifestyle accessories. (Hamilton, 2003, p.95)

While feel-good fuels branded consumerism for both men and women, there are likely to be gender differences. Some think that for women the need to look and feel good is more prominent than it is in men. But this will depend on individuals. Evidently for men displaying power, masculinity, prowess and sex appeal are likely to be underlying factors. For some men, their new, younger wife can be regarded as proof of their success and virility – the so-called ‘trophy wife' syndrome (Siegel, 2004).

The term ‘power dressing' has been applied just as much to women. Wearing ornaments, distinctive clothing and marking the body have been used for distinguishing powerful people since Neolithic times. Perhaps revelling in the display of a very expensive car is just the contemporary version of the biggest and strongest in a bunch of cavemen asserting himself.

12. What is wrong with having designer branded goods?

There is nothing inherently immoral in purchasing recognised quality products. Quality and excellent function cost more. Similarly, there is nothing wrong with enjoying one's quality goods. It is always a matter of balance. Problems arise when there develops an obsession with brands that goes way beyond reasonable quality function towards excessive desire to acquire the mystique and cachet of the brands; here perceived status and consequent brand feel-good have become the driving factors. The desires can then fuel consumer spending that goes beyond reasonable needs and this can distort the use of disposable incomes in the direction of waste and compromise of financial future. It is a matter of fine judgment to determine when branded consumer spending becomes unhealthy. This can also affect physical as well as emotional and financial health: for example platform stilettos are not designed for spinal and postural well-being; the pursuit of the right look has led some into anorexia. Some develop an obsessive psychological dependency on branded products.

The branding process is not only pervasive, it is often perceived as natural, taken for granted and not questioned – just the way things are. There is a danger here that a culturally constructed and commercially motivated process can begin to distort, and perhaps even substitute for, the process of identity development.

Another potential problem is where obsession with branded items may have something to do with a sense of insecure personality and identity. Where there are not enough secure internal identity resources, individuals may have an excessive need for external identity resources which help ‘prop up' their projected self by reminding them that they have status because they are labelled members of a higher class.

In a sense, [branding] provides kids with a sense of self-hood before many of them have even recognised that they have a self … [they] suffer more than any other sector of society from wall to wall selling. They are at least as anxious as their parents about having enough money and maintaining their social class, a fear that they have been taught is best allayed by more branded gear. And they have taken to branding themselves, believing that the only way to participate in the world is to turn oneself into a corporate product. (Quart, 2003, pp. 59, xxv).

How people become conditioned into branded consumerism is also an issue (Twitchell, 2005). While consumer activity is free, some argue that people's perceived freedom and individuality have been seduced and diminished to some extent by living in a commercial atmosphere where advertising creates the dominant social reality / cultural meanings. And this social reality says that the purchasing of branded consumer goods is an essential, natural part of personal identity development.

The individuality of modern urban life is a pseudo-individuality of exaggerated behaviours and contrived attitudes. The individuality of the marketing society is an elaborate pose people adopt to cover up the fact that they have been buried in the homogenising forces of consumer culture. The consumer's self is garishly differentiated on the outside, but this differentiation serves only to conceal the dull conformity of the inner self (Hamilton, 2003, p. 72).

Quart's book Branded: The buying and selling of teenagers (2003) showed how the complex of marketing/advertising/media preyed on young people's identity vulnerabilities and was pushing further into childhood to tap the new retail potential of pre-teenagers – the 11–13-year-olds. Market research has understood the psychology of identity development well enough to plan successful links between branded consumer products and the perceived needs of young people (Montoya & Vandehey, 2003). Advertising imagery orchestrates their imaginations in non-verbal as well as verbal ways, to make them more receptive to brand messages.

Designer clothing brands produce children's wear with the overt aim of establishing brand loyalty at an early age. Research has indicated that young children quickly learn to distinguish the major designer labels in clothing and electronics (Ross & Harradine 2004).

Today's teens are victims of the contemporary luxury economy. Raised by a commodity culture from the cradle, teens' dependably fragile self-images and their need to belong to groups are perfect qualities for advertisers to exploit … They look at every place of children's vulnerability, searching for selling opportunities … Kids are forced to embrace the instrumental logic of consumerism at an earlier than ever age … finding self-definition in logos and products. (Quart, 2003, pp. xxiv, xxv, 95).

When people assume manufactured identities, instead of searching for their real selves, they come together as collectivities of attitudes and elaborate poses rather than real flesh and blood, and this has profound implications for the nature of social interaction. (Hamilton, 2003, p. 88).

Brand consciousness is also being pushed with reference to the lowest age group – babies (Thomas, 2007).

Fussy cashed-up parents are digging deep for the right look.

Baby gear (clothing, cots, prams, nappy bags, feeding chairs and the rest) has gone from the stuff of necessity to that of status – for the parents anyway … But the strange thing about the current obsession for the best, coolest and latest for our babies is that it has nothing to do with our babies at all. (Lunn, 2006, p. 26)

Yet another issue is ethical. There are concerns about the way in which people in poor situations are exploited to manufacture designer goods which are sold at ‘rip-off' prices in more developed countries. Also, when the pursuit of luxury goods goes to the extremes it becomes a moral obscenity in a world where there still remains a great gulf between the rich and the poor.

13. How visual imagery resonates with the contemporary consumerist mise-en-scène and conditions people's thinking and behaviour

People are always in the process of constructing meaning that they use to frame their personal lives, even if this is done relatively unconsciously. And visual imagery can have a significant shaping influence on the way this happens; it ‘clues' them into the prevailing consumerist story or mise-en-scène; and they act sometimes consciously, and sometimes without much consideration, in tune with the prevailing story line with which they are aligned.

Two influential factors are people's basic human need for feeling good and for a sense of belonging. Just as eating and drinking release good feelings, getting positive feedback or validation about how you look and present yourself conveys some feel-good. A simple example: the way that people have adopted ‘onesies' (one piece animal suits) as more popular and acceptable wear in public, and not just as they were regarded earlier as esoteric, and fetish-like party dress ups, illustrates the process. Onesies developed from the small niche fetish group called ‘furries' who liked to dress up in animal clothing but who rarely displayed their ‘animal personae' in public. On TV individuals see others in this clothing and almost unconsciously wonder how they would feel in following that new trend. If their imaginative rehearsal results in good feelings, they will be inclined to take up this dress option. In keeping with the animal wear metaphor, the clothing may even make them feel like a cat generating feel-good pheromones when it rubs itself on other cats or people from whom they want affection and validation. Closely allied with the feel-good is the need for some validation or acceptance from important others. And it is the visual imagery itself that provides the first and often most influential validation; through this, the individual feels an approved member of the onesie wearing community; the feel-good is then enlarged to include the happy emotion of belonging. Feel-good and sense of belonging are closely associated. The first aspect of belonging is whether individual feels at home or comfortable ‘within their own skin'. Then it relates to how comfortable they feel with a particular situation, place and reference group.

The feel-good, in this particular instance, is not of great consequence and is fun. But if individuals become conditioned to rely almost exclusively on the use of externals to generate feel-good, then this could become a health problem. They could spend much time from one day to the next trawling for enough externally generated feel-goods to keep them both occupied and satisfied; the high level of continuous distraction in search of this feeling could inhibit them from thinking more seriously about values that may be important for their lives. It seems easier to get by through depending on externals for your feel-good, personal validation and sense of belonging. A preoccupation with such externals can be the reason that some give little or no thought to questions about meaning and purpose to life – at least to long-term meanings and values because they have only short term interests revolving around externals. And when such people are under stress, they need a lot of external validation to help them avoid feeling that they are ‘falling apart'.

While religion provides people with a package of ready-made meaning for life, many still feel that, whether religious or not, they need to construct a DIY (Do It Yourself) system of personal meaning (Crawford & Rossiter, 2006, p. 215). And a DIY system needs ongoing daily maintenance, more so than the situation where you have a well-established set of religious beliefs to depend on; and thus constructing meaning can become increasingly burdensome.

When people are stressed and traumatised, they have increased needs for personal validation through feel-good and sense of belonging. When church-going people are stressed, they can be validated and supported by the ‘big picture' of their religious faith, which in turn is underpinned by a religious culture. In medieval Christianity, this picture was ‘writ large' in the religious imagery that permeated the culture. The religious, political and social dimensions to life had coalesced giving a dominant, unified meaning system and this was suffused with religious imagery that validated and reinforced the social reality of the time; authority and certainty were key characteristics. Today there is an even more extensive saturation of the culture with images about how life should be lived. But it is the opposite of the medieval system; it is not unified – although there is a strong unifying consumerist undercurrent; it is diverse; there is a strong in-built feeling of uncertainty in human meaning; and there is a taken-for-granted, universal presumption of freedom and individuality as key themes. Political, social and spiritual aspects of life can be disparate and at odds with each other, while the overriding power that conditions the contemporary mise-en-scène is consumerism.

Physically and financially, most people in medieval times led a harsh existence. By contrast, the situation today in Westernised countries shows how great progress has been made in making life longer, more healthy, comfortable, prosperous and enjoyable than ever before – at least for many. But there are indicators that all is not well as far as communities' psychological health is concerned (Eckersley, 2005; Hamilton, 2003).

It is difficult for people today to avoid being influenced by the ‘atmospheric' consumer imagery projected by the media. The images can almost subconsciously reach into human depths making people feel that they are at the centre of their universe. The imagery thematics resonate with people's fundamental desires to want to be comfortable and beautiful, and to acquire beautiful things. Just as medieval Christianity made people feel they were part of a grand divine scheme, contemporary consumer imagery can make people feel a part of something greater – part of the amorphous world of luxury and beauty. There is always a questing for ‘more' – like an ongoing subconscious hope that your life will be ‘upgraded to business class' or ‘a more luxurious car'. In the past, for the majority of people consumption was about survival; now for many it is often mainly about status. Formerly, only the wealthy could realistically aspire to grand residences, comfort and luxury; now the consumerist aspiration is evident across the whole range of people. No longer are the majority people content to live within the limits of what was regarded in earlier times as their ‘station in life'. Now the ‘good life' is available to any who can afford it; recent generations are the first to believe that they have some natural birthright to luxury. There is also the complementary myth that ‘you can be whatever you want to be'. But people often learn the hard way that this is not true: You can want to be whatever you can be, but the limited opportunities and constraints may well stifle this wish.

The various types of ‘reality' television show that ordinary people can have their moments of public fame and make their own distinctive marks on the world. They can identify with McLuhan's (1964) group icon – a media orchestrated imagination of the good life for all. Omnipresent advertising keeps ‘refreshing' and hence re-validating the image of the good life, like a constantly refreshing computer monitor screen. And now a new form of image validation operates through the social networking media. Your own digital self-projection, through tweets, face-book, blogs and selfies, promotes your preferred image of self. This can be validated by your score of ‘likes' and responses – and frustrating and potentially humiliating if your self-publication gets not much of an audience beyond your own self.

The relatively new media and communications technologies have created additional pressures on the development of personal identity – particularly the projective function of identity (Crawford & Rossiter, 2006, p. 94) concerned with the desired image and characteristics the individual wants to display for others. Negotiating these pressures to get satisfactory self-validation has become a prominent concern for adolescents, as well as for many in their 20s to 40s and beyond. For some, it is as if their lives are constantly being framed through the lens of how their present activity might be reported on Facebook – like travelling through life with a reality TV camera constantly recording their every move. For some, a perceived relatively poor performance in these stakes can cause frustration, shame and depression, while for many their digital performance remains a constant source of continuous low level anxiety. De Botton (2004) referred to this as status anxiety. A recent prominent example was reported by Choy (2013) in the documentary Change your race. The practice of using cosmetic surgery to change distinctive ethnic features is becoming more common in Australia's Asian community. In Seoul, South Korea, the capital of de-racialisation surgery, 20% of women have reportedly undergone surgery to make them look more ‘Western'. The documentary identified the great psychological pressure on young Asian women in Australia to conform to their perception of the social reality – that to be attractive and desirable you need to look Western and white. By implication they are feeling that ethnic Asian looks are ugly. The ready accessibility of cosmetic surgery and the force of the visual imagery driving the social reality make some think that if they do not take up that option, they are in fact ‘choosing' to look ugly. And the pressure is even greater if surgically enhanced looks are what their parents want for them.

Articulating these pressures about how to look and perform, and trying to resolve them, have become important tasks for identity development. In medieval life, the pressure was on performing the good life so you could qualify for heaven; now the pressure to perform is about enhancing and maintaining your desired image and status.

Compared with the medieval society where there was little if any choice in lifestyle apart from accepting your lot, today a large range of options is a keynote of the modern consumer lifestyle – it insists that you have options and this is projected in the media imagery as the expression of freedom and individuality. Religion is now regarded by many as an option with an advisory function, and no longer as the overarching and unquestioned meaning system that gave purpose and value to life (Hughes, 2007). The medieval Christian world view was not so much forced onto people but accepted without question; they were not so much constrained within it, but immersed in a social reality reinforced and maintained by interlacing social, religious and political powers; there was little or no thought of challenging this social reality. There are some parallels in contemporary society where it is little escape for the majority from the omnipresent media-portrayed image of the good life. It is difficult not to accept this as just normal reality. People are not constrained or forced to accept it. But it is rarely questioned.

Individuals can now feel that they have a natural right to experience the maximum in the good life. The range of options for making yourself distinctive and unique, and for ‘making your mark', has become huge, and this has economic repercussions through tapping into discretionary income – it is not just through dress, accessories, cosmetics and hairstyle, but through cars and various digital toys, and even through cosmetic surgery, body supplements, steroids, tattoos, body piercing etc. An illusion of unlimited possibilities for self-projection and self-validation is created, and is available at a cost. While people may begin to feel uncomfortable under all of this pressure, they may feel, like their medieval forbears, naturally reluctant to question the larger than life social realities that condition the way they think and feel. One significant difference with the medieval situation is in quality of life. Despite the tensions that modern consumerism can create, it is difficult to challenge or reject a style of life and consumerist philosophy that promise so much comfort, pleasure and emotional validation; and which tantalise with feelings of success, immersion in luxury goods, friends, travel, peak experiences, good food and drink.

Eckersley (2007) acknowledged that much of the progress that has accompanied the growth in consumerist societies has been regarded as positive.

Initially, as changes occurred, we were convinced they represented progress. The old certainties gave way to the exhilarating possibilities of human betterment through economic growth, social reform, scientific discovery and technological development. Even if life's meaning became less clear, life itself became more comfortable, more varied, safer, healthier and longer (p. 41).

But he also acknowledged that the progress had also created its own pathology.

We see growth at the extremes of self and meaning, a loss of balance: pathological self-preoccupation at one end, the total subjugation or surrender of the individual self at the other. A vast consumer economy has grown to minister to the needs of ‘the empty self' (p. 42).

A contemporary identity problem in Australian is Binge drinking, at increasingly younger ages. Click here if you want to look at some analysis of this question in terms of identity factors.

The dominant contemporary mise-en-scène taps into the desire to lead life to the full. And it is not that the consumer objects of human desire are bad in themselves – they are basically good. The crucial matter is the question of balance – how do all the elements in one's actual lifestyle and lifestyle hopes fit together harmoniously in tune with a healthy conception of what it means to be human.

But there remains a further problem here about who is going to decide what this idea of healthy human life means? In practice, this is defined by individuals implicitly through the way they live. Most do not defer to any outside authority about the meaning of life, unless it is the peer groups to which they are aligned. The plausibility of religion as a source of meaning for life has been eroded through secularisation.

Hence there is the challenge for young people to stop and think about these basic questions, and to appraise the cultural influences on them, getting information that may be useful when it comes to reviewing the balance within one's own life in the light of the values they hold as fundamental. An example: An individual may place great store on particular externals for feel-good and self-validation – E.g. having a Prada handbag. But if this pattern becomes too prominent, individuals can be basing their feelings of wellbeing and self-esteem almost exclusively on having particular consumer goods – a relatively fragile and precarious basis for personal identity. As considered earlier, one could argue that a healthy personal identity draws more on internal identity resources like values and commitments than on externals. And there is also the challenge to consider that the range of ideas about what it means to be human needs to be larger than the one individual's limited perspective. It needs community frames of reference, and one significant contributor here is religion. This view sees the critical interpretation and evaluation of cultural meanings as an essential component of education; and one that is particularly relevant to religious education. Hopefully this can inform public debate in the classroom about the ways in which communities and individuals approach these fundamental questions; hopefully too, it can resource the individuals' own personal review of life, a task which is not part of formal education, but which might be taken up in their own time. |

|

The critical interpretation of cultural influences together with personal review of life call on individuals to consider how the extent of their consumerist thinking and practice affects other areas of their lives such as:- their close personal relationships, responsibilities for family and friends as well as for home, commitments, long term goals, work responsibilities, engagement with the community, and even environmental stewardship. If the potential influence of perceived social reality orchestrated by media imagery is acknowledged, people can then make better judgments about their consumerist involvements, hopefully helping them to make wise decisions about finding balance in life.

FURTHER DISCUSSION SPECIALLY FOR TEACHERS

Click here for a brief discussion of why educators need to promote a critical evaluative study of issues like those being considered here -- especially in the subject area Religious Education

15. Conclusion: The importance of being able to study the contrasts in the visual elements to traditional and contemporary spiritualities

Identifying how the mise-en-scène of traditional, medieval Christian spirituality took its cues from the visual elements of Christian culture, has provided a helpful template for analysing contemporary secular spirituality – or more appropriately, contemporary consumerist lifestyle. In turn it provides a platform for evaluating how healthy or otherwise is the overwhelming exposure to contemporary cultural imagery that emphasises consumerism and entertainment. There is a need to educate both adults and young people about the iconography of today's visual world. Many do not pay much critical attention to the way that popular imagery has a shaping influence on their thinking about life and its purpose.

The focus of the visual iconography today is not on the spiritual world but on contemporary lifestyle, experience and living both to the fullest extent. There appears to be little overt place for a formal spiritual/religious dimension in much of the contemporary iconography. So, for many non-religious people, the spirituality that is there is not overt or consciously referenced to a religious culture. Here the spiritual is implied in the values that operate, and it becomes evident when people stop to think and reflect about the meaning and the value of what is transpiring. They have to learn how to detect, identify and articulate the spiritual dimension. So the sort of pedagogy that would help do this is one that is critical, and inquiring. It also means that some criteria have to be established about what is a healthy meaning, healthy identity and healthy living so that there are standards by which individuals might make judgments and decide on actions. This tries to address the danger that they can drift relatively unconsciously into living life at a superficial and materialistic level. It is not that there is anything wrong per se with human experience, with buying things and with the enjoyment of life. It all becomes a question of balance. One of the roles of education is to skill people and prompt them to think about balance.

The approach discussed here can provide a useful pedagogy. However, there is a natural problem when educators seek to get young people or adults to become critical interpreters and evaluators of contemporary cultural meanings. It can be perceived as an attack on their lifestyle. (Parents report that temporarily taking away the smartphone from their teenage children is the most severe punishment imaginable because it is experienced by them as a fundamental threat to their sense of freedom and individuality). Hence the comparative model can be a less fraught way of conducting an evaluation of the influences on contemporary spirituality.

The approach is also fruitful because it addresses another difficulty in social analysis and cultural interpretation. Potentially influential cultural elements like visual imagery tend to be taken as cultural givens or products rather than as cultural processes (Williams, 1980, 1995). If accepted as givens, they are taken for granted and not so accessible to analysis and evaluation. But if they are considered as socially constructed processes, then the production processes themselves are more open to analysis and critique. Showing how the visual mediation of spirituality has evolved is a valuable way of bringing the contemporary use of images, especially those mediated electronically, to educational scrutiny.

The cultural imagery that projects imagined possibilities for life can then be evaluated, and this in turn can help people avoid being just passive consumers of visual culture. Value judgments can be made about how the visual imaginations of life are projected in media and how they serve consumerist and entertainment purposes. This helps people see that it is easy to go along with the dominant modes of living as proposed in cultural imagery, and making sense of life in a relatively unquestioning way. But they can end up being slavish conformists living with a cherished illusion of unlimited personal freedom.

A key purpose in an education in spirituality is to help young people stop and pay more attention to the visual media imaginations that are being offered for consumption. And borrowing from the Australian cartoonist Leunig's (1984) picture of the Understandascope, education can help in developing this instrument in the minds of young people so that they can better interpret and evaluate the visual imagery that everywhere surrounds them, learning how it can affect their meaning, identity and values.

|

| Click here to return to the main identity study page

|